Sunset looking west over the Indian Ocean January 2014 (Photo R de Crespigny)

For the aviation evangelists I recommend the issue of Flight dated 7th March 1914, published by the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom. The list Committee members then included aviation notables such as T. Sopwith and J Moore-Brabazon.

Frank Van Haste emailed me today:

Captain, I note that 100 years ago today (4 Mar 1914), among those present at the annual dinner of the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom, was your ancestor Sir Claude Champion de Crespigny. He would have heard the extensive remarks from the First Sea Lord, Sir Winston Churchill. Thought if you were unaware, it’d interest you.

Thank you Frank. Indeed this issue of Flight is an extraordinary newsletter that shows a glimpse of the intrepid aviators in their fledgling industry as it existed 100 years ago, and how far we have progressed in such a relatively short time.

The discussions included:

Fear of Flight – 1914

… at the high altitudes above 8,000 feet …

- pilots may have a lot of light to throw on the subject, but that they dread to say anything about it, for fear they might be thought less of from the point of view of those not knowing better ….

- many pilots have an awful dread that their engine is going to stop

- Everywhere is space, emptiness, blankness. He is but a speck in the vast expanse.

- Still higher, and yet even higher he may force his machine, and all the previously explained sensations become intensified. Is it then not possible, or even probable that at an altitude similar to that pictured a pilot may become possessed of fears that have no foundation—fears that are born entirely of his own imagination, and having been born, shall become more and more realistic, and, attacking the nerves when they are in no fit state to fight against them, shall take possession of, and dominate the whole mind to the extent that the pilot shall see with his very eyes, the thing which he dreads taking place, with no power to prevent it.

Hypoxia (not understood in 1914)

- Ten, twelve, fourteen thousand feet! The air becomes more rarefied, the brain becomes exhilarated, there is a feeling of lightness about the whole body. With the reduction of the atmospheric pressure, the blood courses more rapidly to the brain, the pulse beats quicker, there is a dawning sense of hysteria. Then arises an inclination to sing and shout, or, perhaps, even an almost irresistible impulse to get out and walk about on the wings.

- At a still greater altitude, when the air becomes even more rarified, this light feeling is probably followed by one of lassitude—a reaction to the previous excitement. The brain becomes dull, strange fancies take possession of it, and it is conceivable that a man may now have thoughts, which, under the circumstances, are more likely to take the form of fears than the previous glorious exaltation. He is up thousands of feet above the earth. Above him, as he looks up, is space— blue, indefinite space, unmeasurable even to the imaginative mind.

- On a related physiological topic, Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) has just released its Flight Safety Australia publication (March-April 2014) that includes an interview “Don’t believe your ears” and video on the topic of spatial disorientation.

Sir Winston Churchill – 1914

My ancestor Sir Claude (QF32 page 14) was one of the 75 pilots that attended the Royal Aero Club annual dinner. Sir Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) was the special guest who offered these perceptions:

- Perhaps flying is one of the best tests of national quality which exists. It is a combination of science and skill, of organisation and enterprise, which affords a more fitting field for the exercise of this quality than many of those games and competitions which are made the subject of international contest. (p 249)

- I do not think we can expect for some considerable time that pleasure flying will be indulged in on a large scale. I am not talking about mere sensationalism, or the very natural desire to see what a new thing is like, but if pleasure flying were ever to be solidly established in this country, it would be necessary that it should be possible to travel across country with a considerable degree of assurance that the passenger would reach his destination punctually and in good condition. And that unhappily is not possible at present. This is a particularly difficult country to fly in. Its land and its physical nature make it incomparably a severer test of aviation than do the conditions which present themselves on the Continent. And until British engineers are able to devise an arrangement of engines or a combination of engines which will ensure that the pilot is not forced to make an unexpected and possibly inconvenient landing it is not very hopeful that flying for the moment will reach a point at which it could be a sure foundation of strong propulsive power for our aviation services. (p 248)

Aerodynamics

There is also a discussion on the stability of different airfoil shapes and using ailerons instead of “wing warping” to roll the aircraft.

Air Crash Investigators – 100 Years Later

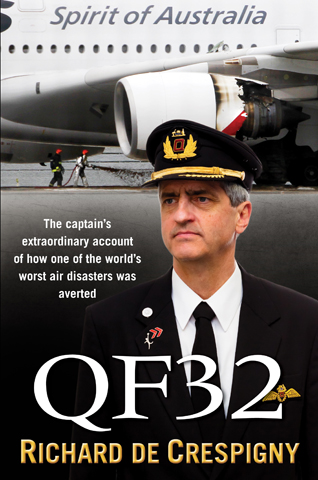

The Royal Aero Club newsletter reminded me of my closing remarks in a recent interview for the production “Air Crash Investigation S13E10 – Qantas 32: Titanic In The Sky”.

At the time of my interview, our story was planned to be the final episode (ever) in the Air Crash Investigators series. So I was determined to use this opportunity to acknowledge my ancestors that had toiled and suffered to make aviation what it is today – perhaps the safest transportation industry in the world.

What a privilege. What a responsibility!

My final words were intended to thank everyone who had contributed to aviation. I wanted to acknowledge the earliest pioneers; those who had assembled in London at the Royal Aero Club Dinner on the 4th March 1914, and their descendants.

I particularly wanted to thank; Armstrong, Boeing, Bird, Boyd, Brabazon, Brentnall, Crossfield, De Havilland, Earhart, Gagarin, Garros, Glenn, Hawker, Haynes, Hinkler, Hoover, Hughes, Johnson x 2, Kingsford-Smith, Kranz, Kuchemann, Langley, Lindbergh, Lovell, Lowe, Ogilvie, McLean, Moody, Orlebar, Roe, Rolls, Royce, Sikorsky, Smith, Sopwith, Sullenberger, Sutter, Turcat, Ulm, Von Braun, Whitcomb, Whittle, Wright, Yeager and Ziegler, and so many more.

It’s a pity that my full statement of appreciation was shortened:

The QF32 story – it’s not about me as the pilot in command of QF32, the pilots, the cabin crew or even my airline. It’s a story of resilience and team excellence where 8 teams pooled the industry’s knowledge, training, experience and worked together to survive a Black Swan Event. It’s about aviation that for the last 110 years has shared their knowledge and experience to made aviation safer for the travelling public.

See also:

- 100 Years Ago in Aviation

- Aviation pathways for Aspiring Pilots (for the 1918 Lancet article: “The Essential Characteristics of Successful and Unsuccessful Aviators”)

Thanks Richard for this great article.

I had a relative who left an audio tape of his life before he passed away. In it he mentions going to an airshow in the early part of the century and mentioned “these two brothers” who brought over their flying machine from America. Pretty cool stuff.

I’ve loved aviation since I was a kid and had my first flying lesson for my 16th birthday. Now at 48. I look back and wonder what districted me from taking up the career. Instead I did an apprenticeship and got into the electronics industry and later the IT field.

I have a private license and still look to the sky every time I hear an aircraft, but I would love to be flying the big machines.

I remember back to pre 2001 when I could show my logbook and get on the fight deck of a commercial flight. Fond memories.

I’ve purchase your book for myself and a friend in the US, who is a Aircrew program designated examiner.

Thanks for all the time and effort you have put into bringing home the big jets safely.

Cheers

Matthew

Captain, thanks for jumping off from my very brief point-out and providing this brilliant look at the breadth of matters touched on in just that one century-old issue of “Flight”. Every time I look into one of those old numbers I’m reminded that we do indeed stand on the shoulders of giants!

For the past few months I’ve been maintaining a blog page (HERE) that looks back 100 years from each day for an item of then-current aviation news…(which is how I came upon Sir Claude’s dinner engagement). It has given me pause to note as I’ve searched out these items, how many of those giants, having been central to advancing the aviation art, “went West” in their 20’s or early 30’s. I think of men like Harry Hawker, Tony Jannus, Lincoln Beachey, Roland Garros, and so many others. Not all that many lived to comb gray hair.

Now, a century on, we fly with a level of safety that we owe to the skill and knowledge they bought and paid for, in too many cases with their lives. So, if nothing else, I hope that they had a memorably wonderful dinner that night at the Savoy.

Frank

Thanks Frank,

We think alike with our respect and admiration for the intrepid aviators who sacrificed so much that our profession would evolve to connect the world just like the steam trains and ships of the century before, and the internet today.

The Lancet may have documented in 1914 that: “the less the fighting scout pilot knows about his machine from a mechanical point of view the better“.

What a paradox then that one hundred years later, through the efforts of those pilots, that the converse is true.

It would have been an honour for us to join those 75 other pilots at the Savoy!

Rich

Richard,

A great statement at the end of Air Crash Investigations.

Even if it was shortened, the “Essence of Aviation” (which is crew teamwork, experience, training, knowledge of your machine plus the essential ability to assimilate and learn on the spot) is what pulled this event through its highest hurdles.

Whilst I have no doubt you and your crew made use of knowledge and experiences documented over the many decades of aviation, I have also no doubt the Aviation Industry will use what you and your crew achieved on that day, as a clear example of what the Aviation Industry has achieved to make our skies safer.