The perils of automation – Aviation, Tesla and the Australian Open

The Australian Open Tennis Championship has fallen for the same automation trap that that the aviation industry has been suffering for the last ten years.

The problem is with technical human-machine systems that are not resilient.

The problem boils down to this – the more you automate a process, the less operators retain their focus on, and intuitive skills for, that process.

Technology and Security are enemies

Automation must only ever be a tool to assist the human – never the only option to take over. Ignore this rule at your peril.

The terms “High-technology” and “security” are oxymorons. That’s because Technology and Security are enemies of each other.

In his book “Beyond Fear”, world data expert Bruce Schneier wrote (page 9) about technology:

Technology is an enabler. Security the opposite. It tries to prevent something from happening.. That’s why technology doesn’t work in security the way it does elsewhere, and why overreliance on technology often leads to bad security.

Whilst technology is the enabler, security is the technology brake that is always trying to stop things from happening.

That’s why technology can’t synergise with security the way it does in other spheres (accuracy, cost, speed, time). And that’s why over-reliance on technology often leads to bad security and increased risks.

Humans must learn to survive without automation or when the automation fails. When the technology doesn’t do what we want, we must be confident to turn the technology off and either continue the task manually, or stop the task.

Aviation – Auto Thrust

Pilots must never rely on automation.

For example, auto thrust systems in aircraft are simple systems, designed to support the pilot but never outvote or overpower them.

In Boeing and Airbus aircraft, the auto thrust systems can be overpowered or disabled simply by moving the thrust levers. When the auto thrust system fails, pilots simply need to move the thrust levers by hand, in the same way that a driver of a car presses on the accelerator pedal.

Practice makes habits. The more you automate a process, the less operators retain their focus on, and intuitive skills for, that process.

Yet many fatal B777 and B737 accidents over the past few years have occurred because the pilots trust the computers too much, don’t understand how they work, and are sceptical or underconfident to disconnect them or override them using brute force. This overconfidence in automation and underconfidence to disconnect it started to appear in aviation in the early 2000s.

Curiously, many Boeing pilots who criticised Airbus auto thrust systems, failed to appreciate the underpinning logic and Human Factors (ergonomics) of the Airbus design, that always requires the pilots to manually advance the thrust levers to commence a take off or to go-around. That first habitual (hippocampal) physical forward movement triggers the auto thrust system to engage and assist the pilot. In the event that the Airbus auto thrust fails, the engine thrust setting reverts to the selected thrust lever angle that will (unless in the case of engine failures) always produce sufficient thrust.

Furthermore, some Boeing pilots rely too much on automation. Some just press buttons to command the auto thrust to advance the thrust levers for a take off or go-around procedure rather than pressing the buttons to select the desired automation mode, then physically pushing the thrust levers forward to ensure the thrust actually does increase. These pilots trust the auto thust to physically advance the thrust levers for them – a trust that has in one recent event, ended in misery. Putting one hundred percent trust in the auto thrust can have fatal consequences when the auto thrust is operating in a mode unexpected by the pilot, or not understood by the pilot or when the auto thrust fails.

This problem is due to a lack of Knowledge, Training and Experience – three of the elements of resilience that I detailed in FLY!.

This problem must be fixed.

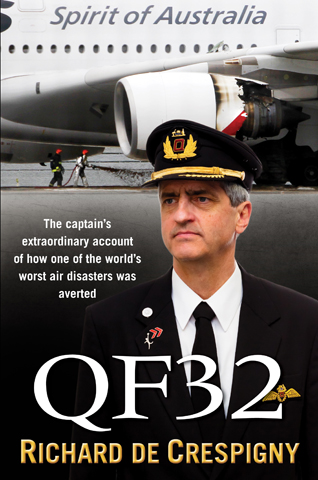

Note: In my book QF32 at page 160, I discussed how I reverted to manual thrust in the seconds after the engine exploded. At page 257, I documented my problems with the autopilot that disconncted many times whilst I flew the final approach to land. When it became more of a nuisance that a help, I kept the autopilot disconnected and flew the rest of the approach manually.

Recent Incidents:

- https://www.airlineratings.com/news/maintenance-pilots-focus-indonesian-737-crash-investigators/

- https://www.seattletimes.com/business/boeing-aerospace/faa-safety-engineer-goes-public-to-slam-the-agencys-oversight-of-boeings-737-max/

Tesla – Autopilot

Drivers must never rely on automation.

Tesla’s autopilot and other automotive autopilots are not replacements for the sentient human mind. In SAE’s scale of “Levels of Driver Automation”, a scale from zero to five, Tesla”s autopilot is ranked at just level 2. (Current Boeing and Airbus aircraft would also satisfy just Level 2)

Any autopilot is only as good as its extremely limited senses, computers and actuators.

Humans have four million input nerves to the brain (senses), 86 billion neurons, 100 trillion synapses (computer), and 650 skeletal muscles to move controls – vastly more than any current autopilot. Telsa automated cars are only resilient because the human must take over control when the simple autopilot fails.

See also: https://landline.media/study-the-more-you-automate-driving-the-less-drivers-focus/

Tennis Australia – LET Sensor

Tennis Australia (AO) has also fallen into the automation trap.

The Australian Open tennis courts have new sensors to detect the ball bouncing outside the lines and to detect LETs during the serve.

Unfortunately the LET sensor has no redundancy when it behaves spuriously as it was suggested to behave last night. Nick Kyrgios believing the sensors to be incorrect, begged the umpire to “turn the machine off” then stated “I’m not playing until you turn it off”.

Whether the sensors were correct or not is not the issue. The issue is that the sensors were suspected to be faulty and there were no procedures to validate the sensor, or to fix or mitigate a failure. (There were no video cameras to check the sensor’s accuracy, and AO appeared to have no procedures to refer to when the sensor was suspected faulty.)

A risk assessment for the new technology should have resulted in procedures being developed for the umpire to validate the sensor, or turn the sensor off and manually take over – something as simple as assigning a person to listen to and feel the net.

Lessons

There are three key lessons in these three cases.

- Firstly, as the number and complexity of machines increases in our lives, the designers must ensure that there are always procedures for humans to shut down machines, take over manually and survive. The only constraint for this disconnect switch is that it should not become in itself, a single point for a critical failure. (see note below)

- For pilots, Tesla car drivers and indeed every person using complex machinery, it’s critical that humans have the Knowledge, Training and Experience to operate the machine in the manner that it was intended to be operated. In the event that the automation is not performing as expected, operators must also have the confidence to, and the knowledge how to, disconnect the automation and resume manual control.

- Practice makes habits. The more you automate a process, the less operators retain their focus on, and intuitive skills for, that process.

Coral and I wish you a safe, healthy and happy COVID recovery. We wish you the best to FLY!

Note: Today’s Airbus and Boeing aircraft contain multiple flight control computers that host the Fly By Wire flight control system logic. Both manufacturers have different methods to degrade the control laws from Normal Law (when everything is working) to Direct Law (when dependent systems fail). Boeing provides one switch to command Direct Law. Airbus requires at least two switches (in many optional combinations) to be turned off to effect a change to Direct Law. Which method is best? Let me know if you are interested to discuss.

Updated 8 March 2021

Enjoying your Fly book Richard , which I’ve just gotten a hold of and am three chapters in – full of wisdom and ideas.

I had a question as someone interested in aviation but never flown – I thought it curious that you posted examples of Boeing pilots being over-reliant on automation and not adapting well when the automatic assists failed , sometimes causing accidents.

As someone who has flown both Boeing and Airbus craft in your career do you think Airbus pilots are more aware of the limitations of automatic systems – given that those planes are built from the ground up with FBW and computer control integrated from the beginning? I strongly wonder this with the whole MCAS situation where to reduce training costs the 737 Max had automation put in to make it fly like a 737-NG despite the engine overhangs (from memory) causing the Max to pitch up under thrust much more than the older aircraft.

Hi Francois,

I recently discussed automation in Boeing aircraft because of the recent spate of accidents in Boeing aircraft that have many contributing factors including some pointing to the pilots, their knowledge, skills, training and experience.

There have been many accidents in Airbus aircraft that were due to the same reasons.

The fundamental problem is that, as the use of automation increases, the basic knowledge, hands on skills and experience of the operators has been permitted to decrease.

The benefit of employing increased automation (without mitigating the loss of hands on experience) comes at the cost of reduced resilience when that automation fails. It is for this reason that I believe that the new highly automated aircraft are more challenging to fly than the simple, older and less technical variants.

The problem is when high tech equipment is employed to save money, but at the cost of the worker’s knowledge, experience and skills. This has been the cause of many industries drifting to failure.

In summary, I am not biased towards one manufacturer more than another. Technology and security are enemies. I am concerned that the industry that blindly chases ever higher tech, is at risk of reducing their resilience.

Thanks for the reply – now I understand you were talking about some recent incidents with Boeing aircraft , and there’s no reason why pilots with other manufacturers can’t fall prey to the same over-reliance with automation , although I wondered if type experience might play a part.

“The problem is when high tech equipment is employed to save money, but at the cost of the worker’s knowledge, experience and skills. This has been the cause of many industries drifting to failure.”

Short term profit , long term pain and ruin as skillsets are lost. I agree , with more complex aircraft the pilots would need to have a mental model to understand the automation and the way the computers like ECAM “think”.

Thank you very much for the wonderful update in what is happening in the Aviation industry.

Kinds Regards Michael o Connell.

PS. Hoping soon to get the last book that Captain Richard de Crespigny wrote.

Absolutelt correct Richard, well said

You are so right! And we seem to be in the process of being forced into getting more and more “safety” devices in cars.

Driving requires a large portion of one’s consciousness if one is to always understand what the traffic in the immediate vicinity is doing and what the traffic ahead is doing and the number of overtaking cars behind. The human mind is unsuited to maintain that level of concentration if not intimately involved in the task.

I am/was a “little pilot” as one lady put it when I told her I flew a Cessna T210 and 337 (and have I bet about 5% to 10% of your hours) but I know enough to understand that autopilots can turn themselves off with little or no warning and if your scan is not constant the plane may no longer be doing what is expected. But that awareness takes several seconds to surface,

OK in an aircraft in flight as separation is generally in large fractions of miles and other than landing or takeoff the lost time can be accepted but in a car on the freeway there are inches, not miles to worry about!

Sorry for the rant but I worry that “automotive safety” will be seriously compromised by the automation. Most people drive on their internal autopilot and are not completely conscious of the road! They will drive right up to a truck and slow down and pace it, or they pass and slow down and keep you in their blind spot which drives me bats as they obviously no longer know you are there. I have learned it is better to accelerate while passing so that the driver does not match your speed and stays in my blind spot!

Thanks for listening to a rant that you are no doubt completely aware of and need not be reminded of!

Richard this is so true even in my industry(Engineering) where we rely so much on simulations and lack the experience to validate the results without use of a computer, what ever the spread sheet or computer program spits it is taken as gospel-you inverted the logic in QF32 and saved lives let alone the multimillion $ machine, thoroughly enjoyed your book,

What is it that the airforce teaches its pilots that the commercial airline don’t do- both you and Sully are ex airforce pilots where there was 99% for that machine to dropping off the sky you did an absolutely amazing job-great job Richard

Great article Richard! The Tesla autopilot (or any other type of car autopilot) are a great concept but parts of the technology really concern me. In a scenario where a pedestrian steps off a kerb in front of a car that will not be able to stop in time, but the car’s only avoiding option is to steer in front of a truck or into a tree…what does it do? Who decides at what point whether the autopilot saves the pedestrian or the occupants of the vehicle? Is it the manufacturer? The owner of the car? I guess it could return control to a driver to decide, but would they react in time?

I trust that an airline pilot will have sufficient Knowledge, Training and Experience to know when and how to intervene. I don’t trust that the average driver will.

Thanks for explaining this so well.

Andrew it gets worse if Sensors or GPS fail s like you said who is liable in case of an accident

The pilot/driver is responsible for safety. Automation can be a contributing cause in an accident, but it’s the pilot/driver who is ultimately responsible for the outcome.

Completely agree. Part of Tesla’s problem is the marketing – calling the feature “autopilot”, yet it’s not really an autopilot. Like the car, the tennis system doesn’t have the redundancy or resiliency to detect an issue in time for the human to regain situational awareness, assume control and take corrective action without it being “fatal” (i.e. an outcome where the human would have decided not to use the automation if they’d known).

Out of interest, when a plane like a 380 is on autopilot, how often do you need to check it’s still performing the way you expect, and what is the minimum reaction time assumed for you to take control in the event the autopilot decides it can no longer perform it’s task?

Hi Greg,

Pilots do not ready newspapers or watch movies during flight. They are constantly monitoring the cockpit, instruments and outside for any activity that does not match their predictions.

When something fails to match the predictions the pilot then works out where they are, where they want to be, then acts to correct that difference. If analysis detects the autopilot to be malfunctioning, or if you just don’t know what or why it is doing something, then you MUST disconnect the autopilot, resume manual control, establish the aircraft back on path, and then and only then look at diagnosing what happened or what to do about it.

In summary, pilots don’t really mind when things go wrong, because (on average during my career) things go wrong at least once every hour. What’s important when things go wrong is not talking about it being wrong, but taking over control, reestablishing safe flight, and then and only then, analyse the fault.